There’s a lot happening on the Internet these days that reminds me of the recovered memory, ritual abuse and multiple personality disorder crazes of yore. It’s not just an erosion of critical thinking skills as we retreat to online echo chambers, or the dissociative identity disorder nonsense that’s rampant on TikTok; it’s an all-purpose cultural identity crisis, and just about every demographic is having one. As a cranky lesbian, for example, I can spot “AFABs” who’ve not completely worked through their trauma, whatever its origin, not only by their tragic hair and identical facial piercings but by the convoluted and sometimes adversarial nature of their sexual and gender identities and the myriad somatic disorders they collect like so many stuffed animals.

If you have no idea what I’m talking about, I am envious of you. If you’re a liberal woman in your early forties or under, and particularly if you’re gay and active on social media, you’re probably familiar with the hoarding of marginalized identities — the more easily weaponized, the better. Because these identities aren’t only alluring as veritable ATMs of social currency, they’re a shield from criticism in some communities. Few are held in loftier esteem online (by themselves, if no one else) than someone whose Twitter or Reddit bio is a collection of abbreviations and acronyms indecipherable to most outside their orbit.

Their gender and sexuality might be “NB, trans, pan, poly, ace, queer AF,” like a vegan burger with everything on it. Then there’s the compulsory proclamation of mental illness or other neurodivergence (autism, ADHD and CPTSD are currently all the rage, but if you unmask the Scooby-Doo villain causing the bulk of their problems, you’ll usually find that it was a personality disorder all along, even if they also have other legitimate diagnoses). Finally, we move on to physical ailments that are often accompanied by zebra or wheelchair emoji: hEDS, POTS, MCAS, ME/CFS, FND, Groat’s disease, etc. It tends to sound more exotic than it is. They might be, or have, a few of those things, but not 15 of ’em. Because their social lives frequently exist more in theory than in practice (i.e., they live on Discord), and because their ailments are often self-diagnosed (due to medical ableism, they’d contend), it’s mostly abstract anyway, though they’d protest it’s gatekeeping or something similarly disqualifying to say so.

Experimenting with identity is a normal part of our development, particularly when we’re young; it’s an extension of playing dress-up as toddlers. But I am increasingly wary of how this unfolds both on and off the Internet. It doesn’t do autistic people, tic disorder patients or epileptics any good, for example, to be represented on popular platforms by attention-seeking goons without those conditions who obliviously recreate offensive routines they learned online. It’s not helpful for gay people to be lumped in with straight attention-seekers who’ve internalized Aunt Ida’s dismissal of heterosexuality as “sick and boring” and call themselves queer because they like rainbows, Drag Race and sarcasm. Similarly, an eagerness to broadly label uncomfortable things “traumatic,” “toxic,” “gaslighting” or “abuse” has its own deleterious or trivializing effects, though you risk being called problematic or a gaslighter yourself if this concerns you.

I could go on and on about the corrosiveness of these trends. About the dangers of being taught by the Internet that you are your mental illness, and that certain diagnoses preclude you from accountability, independence or any kind of meaningful existence. About the perils of suggesting that anyone who identifies in some nebulous way as physically disabled is automatically and unquestionably physically disabled — and that it’s “internalized ableism” for a Redditor to have second thoughts about, say, becoming an ambulatory wheelchair user against their doctor’s advice at 16 because of a self-diagnosis they reached after falling down the wrong Internet rabbit hole. And I’m made particularly uncomfortable by it when I revisit 1980s and ’90s-era TV movies like Fatal Memories and Betrayal of Trust that highlight how all-in we tend to go on pop psychology that doesn’t pass the smell test.

This growing discomfort with the relentless pathologization and politicization of every last detail of our personalities and experiences, and how often it intersects with paranoia (including conspiracy theories) or manipulation, has compelled me to take a fresh look at books like Sybil, When Rabbit Howls, Michelle Remembers, Remembering Satan and Making Monsters: False Memories, Psychotherapy, and Sexual Hysteria. Michelle Remembers, published in 1980, is the most notorious and shameful of these titles, not only for its unbelievable tale of ritual Satanic abuse*, but because of co-author Lawrence Pazder’s involvement with many of the hysteria-fueled legal witch-hunts it inspired. Sensationalizing things further, Pazder was a psychiatrist who later married the eponymous Michelle Smith, his patient.

How Michelle Remembers was ever taken seriously should be difficult to fathom in 2023, but I agree with Sean Horlor and Steve J. Adams, directors of Satan Wants You, an upcoming documentary about Pazder and Smith, that it seems as timely as ever. (Not only are these conspiracies of abuse echoed in QAnon nuttery, it’s easy to picture a contemporary iteration of the duo with a podcast empire, robust TikTok following and endorsement deals with scammy apps like BetterHelp.) I never thought I’d read a kookier psychologically-oriented introduction or preface than what was featured in Hedy Lamarr’s Ecstasy and Me: My Life as a Woman, until encountering Thomas B. Congdon Jr.’s publisher’s note in Michelle. It begins with a lengthy and meaningless rehash of Dr. Pazder’s “impressive” credentials before moving on to this, which I suggest reading in the voice of Dana Carvey’s Church Lady:

Two experienced interviewers journeyed to Victoria and talked to Dr. Pazder’s colleagues, to the priests and the bishop who became involved in the case, to doctors who treated Michelle Smith when she was a child, to relatives and friends. From local newspaper, clergy, and police sources they learned that reports of Satanism in Victoria are not infrequent and that Satanism has apparently existed there for many years.

— Michelle Remembers

Next comes an assurance that Pazder’s extensive notes of Smith’s sessions were “read and digested” (what heartburn that must have caused) and that videotapes and audiotapes were reviewed and pronounced “powerfully convincing. It is nearly unthinkable that the protracted agony they record could have been fabricated.” I’ll pause here to give anyone who works in the mental health fields, or in publishing, a moment to collect themselves.

Congdon assures us that both Pazder and Smith “were interviewed at great length” and their accounts were again deemed credible, in no small part because “Michelle’s distress during these retellings, the fresh pain they obviously inflicted on her, seemed to indicate that this was not some fantasy concocted for commercial gain.” The notion that financial self-interest or bold truth-telling are the only options here, and that no weight is given to whether the stories could be false and Smith’s pain and self-belief could be genuine, is stupid enough on its own terms. And it’s especially strained when followed by speculation that the authors’ “relentless insistence” on the accuracy of the jacket text “was hardly the mark of the charlatan.”

But the knockout punch, what really puts Congdon’s note in the hall of fame for me, was this:

Along with Dr. Pazder and the Church officials who know her so well, I believe that Michelle is not a hysteric, not even a neurotic. She seems as clear as a glass of well water. She appears to be one of those rare people, like Joan of Arc and Bernadette, whose authority and authenticity are such that they can tell you things that would otherwise be laughable — yet you do not laugh, you do not dismiss or forget.

— Michelle Remembers

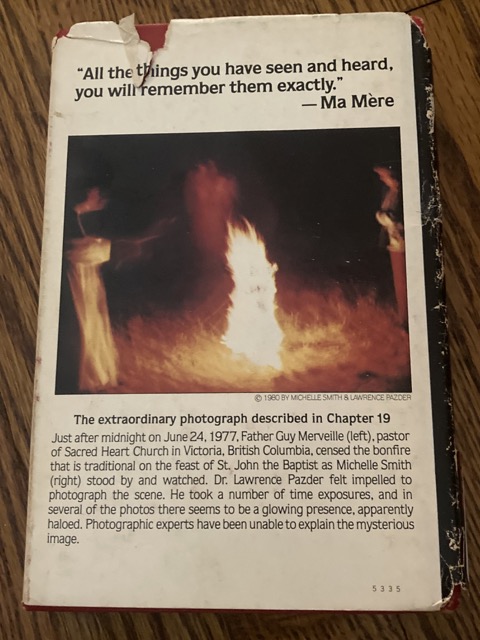

Joan of Arc and Bernadette! This book should’ve come with a shovel, and Congdon’s note is only the beginning. It’s cover-to-cover bullshit; even the back of the dust jacket isn’t spared. It’s easy to laugh at this, but 40 years ago it ruined many lives, and the conditions and impulses that made it popular then endure, and are just as dangerous today.

* To give you an idea of how berserk Michelle Remembers is, I will turn to a random page and transcribe some of what it contains: “In her frenzy, she grabbed what was at hand — the snakes. Scrambling to the bottom of the stepladder, she gathered them up by the handfuls and pushed them through the effigy’s eyes. […] The children saw the snakes flying out of the eyes, and they danced faster and faster. […] She rushed down the stepladder again and picked up more snakes. And the decaying pieces of the baby.” By the middle of the page, Michelle is naked and “streaked with blood,” before she is attacked by a demonically possessed woman who vomits all over her while “celebrants danced and did strange things to each other, including the children.” Incidentally, that was the original opening to Pippi Longstocking, before an editor intervened.

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn a small commission from qualifying purchases.