All four installments are now complete. Sorry for doing it piecemeal.

This month has been off to an inauspicious start, but I should have some good news to share soon, possibly within the next few days. And if anyone liked the Whirlpool post, I might try something similar with whatever I watch this weekend — just a few screen caps and dumb jokes about an old movie. In other viewing news, once we were done with our Acorn streaming trial, Crankenstein and I switched to BritBox, which we usually only get for a month or two each year through Amazon.

We recently finished the first season of The Cleaner, the very dark but uplifting brainchild of Welsh comedian Greg Davies, who writes and stars. I’m reluctant to say much about it because it’s an experience that should be as unspoiled as possible, but if you enjoy black humor and offbeat humor, hang in there through the weirdness of the first couple episodes and you will be richly rewarded. If you love Helena Bonham Carter when she’s particularly strange or unlikable, you’re rewarded sooner than that.

On to February’s library borrows…

“Go gay with Garbo!” read the posters for Two-Faced Woman, and it’s only natural to reply “Don’t mind if I do!” But there’s little gaiety in this dud, which fell victim to the censorious demands of the Catholic Legion of Decency. It’s remembered mostly as trivia, the ignoble last hurrah of Garbo, but I’d argue the bulk of her films were average at best. We watch her today because of that face, and because of the so-called mystique that was only truly mysterious to those who bought into the heterosexuality pap.

Others of her ilk recognized it for what it was: her je ne sais quoi was more of a je ne gay quoi, if you’ll forgive the pun — Garbo had the face of a sensuous angel and the spirit of a long-haul trucker or the captain of a women’s national soccer team. Whether vowing to “die a bachelor” in Queen Christina or planting Sapphic kisses on costars in that film or The Painted Veil, she was a heartthrob disguised as a leading lady. If you’re familiar with the viral Reductress joke about Rachel Weisz (the headline’s funnier than the article), that was Garbo, who enjoyed popularity on a far more massive scale.

I’ll need to revisit some earlier Garbo soon for something I’m working on, and decided to rewatch Woman as a sort of reverse starting point. As for the rest of these borrows, Hot Saturday is a pre-Code film about scurrilous sexual gossip, so it’s only fitting that it features Cary Grant and Randolph Scott. G Men is a Cagney gangster flick, except this time he’s not a criminal, which is a little sad. It costars Margaret Lindsay, who I mentioned at least once on Cranky Lesbian during its original run. For the uninitiated, she was a lesbian actress who didn’t bother with a lavender marriage, which probably cost her roles in the long run.

Cry Danger is another noir; Heat Lightning and Finishing School are more pre-Codes. Where Love Has Gone is a Harold Robbins adaptation (i.e., a slog) with a cast — Joey Heatherton, Susan Hayward, Bette Davis, Jane Greer — more intriguing than the material itself, a cheap reworking of the Stompanato case. If that doesn’t ring a bell (it won’t for Crankenstein), it refers to the murder of Lana Turner’s rough trade boyfriend by her teenage daughter, Cheryl Crane.*

Crane’s an octogenarian now whose notoriety seems due for a revival. Between her family drama, legal ordeal, glamorous looks and lesbianism — she’s been ‘out’ forever — she has long been a cult figure among certain older gays. Her introduction to a younger crowd will probably come via a limited series retelling of the crime. Hopefully the rights to her 1988 memoir, Detour, are kept out of Ryan Murphy’s mitts. I’d recommend this old Los Angeles Times profile by Paul Rosenfield if you’d like to learn more about her.

There we have it for last week’s borrows. First update below, more coming soon.

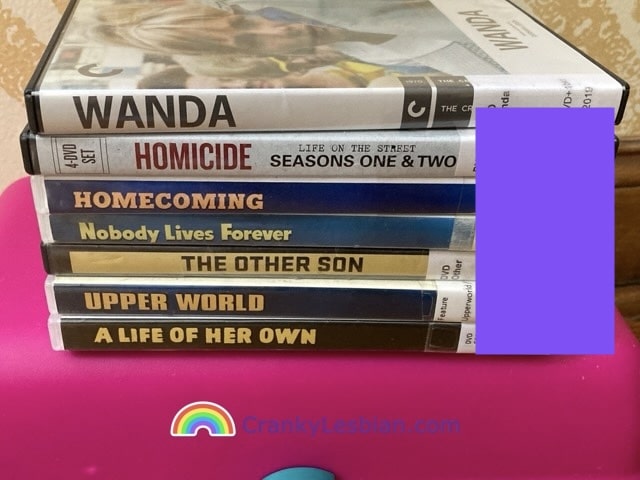

Updated 3/3/24 with the second week of February, which included both movies and episodic television. First up was Homicide: Life on the Street, which I watched occasionally as a teen. Its reputation is legendary and I’ve read the David Simon book on which it was based, but seeking it out for a proper start-to-finish viewing kept slipping through the cracks; Andre Braugher’s death last year was the push I needed to finally do it.** The first two seasons span only four discs due to low episode counts — nine in season one and four in season two.

Upperworld (1934) was one of the last pre-Codes and is nothing special as either a crime or marital tale, but I was curious about Ben Hecht’s story credit. The cast includes Ginger Rogers and Mary Astor, whose hair was usually fascinating in everything she did (even when the screenplays were not). If you have any interest in Astor and managed to avoid Edward Sorel’s Mary Astor’s Purple Diary: The Great American Sex Scandal of 1936 when it was critically lauded a few years ago, my advice is to continue ignoring it. I still remember it quite vividly but more for what it revealed about Sorel’s peculiar appetites than anything it said about the unlikely object of his obsession.

Nobody Lives Forever (1946) is a Jean Negulesco noir with John Garfield, and though most of us probably think first of Humoresque or Johnny Belinda when we hear his name, Negulesco’s style was quite compatible with noir. That said, I’d recommend Road House (with Ida Lupino and Richard Widmark) over Nobody. Homecoming, from 1948, features an illicit WWII romance but is as boring as every other Clark Gable/Lana Turner pairing. Anne Baxter costars, which reminds me — I’ve met one of her daughters several times socially but only learned of her parentage belatedly, when a shared contact referenced it in passing. If our paths ever cross again and the subject of Baxter comes up, my only question would be “Did she observe any strange shenanigans on the set of Walk on the Wild Side?”^

In George Cukor’s A Life of Her Own (1950), Turner’s a model whose married lover (Ray Milland) is reluctant to leave his handicapped wife; it’s hardly Sirkian and not worth making any special effort to seek out, but it was better than I expected. Then we have The Other Son (2012), a French film that I borrowed because of Emmanuelle Devos without realizing it’s already free on Tubi, along with Perfumes and several other Devos movies. It’s about two families, one Israeli and the other Palestinian, learning on a long delay that their sons were switched at birth. Critic Michael Atkinson once called Devos “she of the relentlessly fascinating Picasso face,” which was accurate enough; hers is one of the most arresting and expressive faces in modern film.

Finally there is Wanda, which also streams on HBO Max. It’s best to watch this one without knowing anything about it. Then, once it’s over, read a bit about director Barbara Loden and the reception Wanda received in 1970 and where its reputation has gone since then. In some ways it tells a story as interesting, or more interesting, than Loden’s itself.

Note: This writeup took longer than I expected, so I still have two more sets of February borrows to get through later in the week.

Updated 3/4/24 with what I borrowed in the third week of February. During this time I was still busy with the Homicide set.

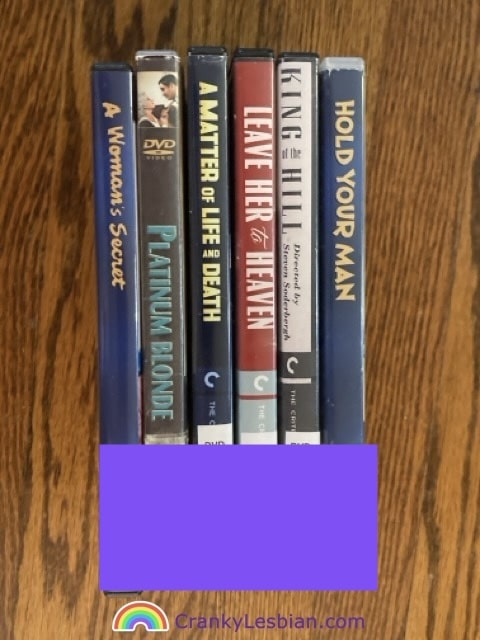

First up are the titles that I requested, starting with 1931’s Platinum Blonde and 1933’s Hold Your Man, both Jean Harlow pre-Codes. I’ll admit that her sex appeal often eludes me; facially she’s almost identical to her mother, and the bleached hair and razor-thin painted-on eyebrows aren’t my cup of tea. Her face remained iconic even as her films faded from public memory, making it easy to forget her body was a major draw at the apex of her fame nearly a century ago. In a roundabout way, Harlow’s body is why I’m reevaluating her career: I’d like to know more about her poor health and premature death, so I’m reading David Stenn’s Bombshell and it’s changing some of my perceptions of her work.

A Woman’s Secret is a Nicholas Ray noir from 1949, adapted by Herman Mankiewicz from a novel by Vicki Baum. It’s convoluted and silly but Maureen O’Hara and Gloria Grahame shoot each other some decent looks before a gun goes off. The three Criterion discs were all spur-of-the-moment pickups, the most sentimental of which was Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death, which takes a familiar plot — whether someone who was meant to die should be allowed to remain on earth — and turns it into something beautiful that always makes me cry. I’ve resisted purchasing individual Powell discs, lest Criterion release one giant set, but my resolve is being tested by its recently announced (and long overdue) rerelease of Peeping Tom.

King of the Hill (1993) is Steven Soderbergh’s best film, a memorable look at a boy coming of age in reduced circumstances among colorful characters in St. Louis during the Depression, while Leave Her to Heaven is something everyone ought to be familiar with already. If you aren’t, it’s required viewing across many categories: melodrama, noir, psychological thrillers, character studies, Gene Tierney, and cinematic portraits of personality disorders. It’s not as physically violent as Play Misty for Me, Misery or Fatal Attraction, but it gets emotional cruelty right in a classic scene made all the more haunting by Tierney’s icy composure.

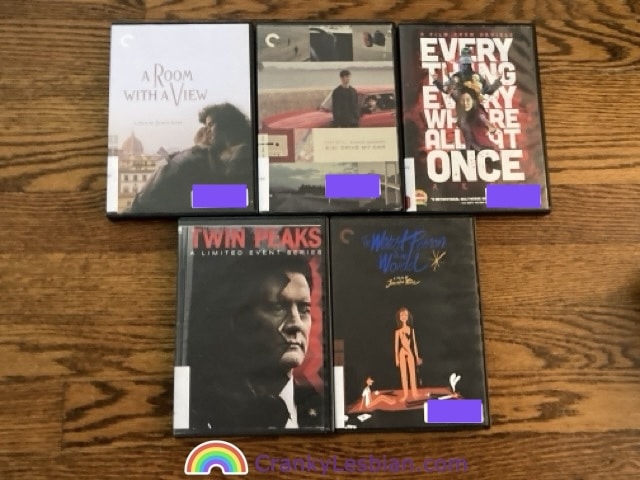

My final borrows of the month were selected while browsing. Everything Everywhere All at Once is still next to our TV; I’ve been saving it for a time when Crankenstein can pay closer attention than she normally gives our viewing. Twin Peaks: The Return is beneath it and I’m undecided on whether to watch it. Despite having seen the original series years before meeting my former partner, our joint viewing of it during the time we were displaced from our apartment was a special enough experience that it may have landed on my “Don’t Play That Song” list.^^

A Room with a View was a rewatch because I needed a palate cleanser after Helena Bonham Carter’s hilarious but horrifying guest spot on The Cleaner. Drive My Car and The Worst Person in the World were both new to me. I enjoyed them but preferred the former; the latter was primarily on my radar because Best Friend loved it and called it “basically a Danish Annie Hall” while ranting about Renate Reinsve’s Oscar snub. I generally refrain from discussing this in mixed company, but few comedy writers were more influential to me as a teen than Woody Allen, other than maybe Preston Sturges.

* Crankenstein and I are a mixed marriage, as we joke, in that she’s resolutely lesbian in her sensibilities and I’m basically an elderly queen. For the love of Mary Martin, she was a proud hairy-legged drum circle participant in her youth! I’m always fearful that one day she’ll stop shaving her underarms and drag me to a commune where everyone talks about their feelings over “nut loaf, lentil loaf and tofu of various descriptions,” which were staples at the granola lesbian potlucks she attended as an undergrad. She’s probably equally worried I’ll spend my retirement in caftans, bitterly arguing about who was the best Vera Charles and randomly shouting things like “No one could dress Kay Francis like Orry-Kelly!”

** While awaiting my turn at the library, Crankenstein and I paid our respects to the brilliant Braugher by rewatching our (many) favorite Captain Holt episodes of Brooklyn Nine-Nine. As a teenager I was often likened to Darlene from Roseanne or Daria’s own Daria by friends, classmates and family, due to our shared short stature, dark hair, monotones and sarcasm. But if you ask Crankenstein which fictional character perfectly captures my essence, she will answer “Ray Holt” before you’ve finished the question, and I take that as a compliment.

^ That’s not a knock against Baxter; I’d limit myself due to politeness, not disinterest.

^^ “Don’t Play That Song (You Lied)” was a Ben E. King hit in the early ’60s that Aretha Franklin covered in 1970. As much as I adore King (both solo and with the Drifters), it’s Franklin’s marvelous version that became one of my favorite songs. I’ll explain this more in a future post, but I have an unofficial list of “Don’t Play That Song” movies, songs and TV shows that I try to avoid to spare myself particular heartaches. It doesn’t have to be romantic; it could involve memories of Felix before he lost his mind or a rough patch in my teens or early twenties.