I found an old Modern Library edition of Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams at a book fair when I was 11 or 12, its dust jacket tattered but mostly intact, and purchased it with great excitement, convinced it would unlock insight into my unconscious that might allow me, perhaps, to finally understand myself. That didn’t happen, of course, and later I came to realize that my beliefs about dreams were more closely (if still imperfectly) aligned with Jungian dream theory, which rejected Freud’s endless Oedipalization of everything.

Yet my dreams weren’t compensatory, either, as Jung eventually believed dreams were. On the rare occasion that I remembered them at all, they were remarkably uneventful. My sister, whose dramatic dreams often found her in life or death scenarios where carnage would ensue if she didn’t take swift, decisive action, was amused by the mundanity of my unconscious. Meanwhile, it exasperated my former partner, who was nightmare-prone and complained that my dreams — like the one about grocery-shopping and finding the eggs had been moved — were tangible proof of an untroubled psyche and a life that had been too easy.

Throughout my childhood and into my twenties, I was plagued by two recurring dreams: one in which I needed to scream but couldn’t, and another in which I rose to the ceiling, unable to lower myself or control my movement as I floated from one corner of the room to the next. A conventional interpretation of the latter would’ve been “You felt ungrounded,” while a more forward-looking Jungian approach might suggest an incipient awareness of a movement disorder to come. Personally, I wasn’t sure what it meant; I just wanted it to stop and was glad when it did.

In my teens, a third recurring dream joined the rotation: visions of a faceless woman, whose hair color and complexion became familiar, welcome sights over the years. Though I didn’t know who she was, I was at home in her arms and knew we loved each other. When I eventually met her in real-life, those dreams of her ceased, but not before she featured — this time with a face — in the absolute worst dream of my life, one that still leaves me shaken years later when I reflect on it, in which something horrible happened to her that I was powerless to stop.

Since the only dreams more boring to us than our own are those of other people, I will wrap this up, but not before getting to the heart of why I wrote it. About eight years ago, I was prescribed a medication, Plaquenil, that I still take today for arthritis; it’s an antimalarial that was found to mysteriously treat some autoimmune diseases. Not only did it reduce swelling of my joints, it stopped the erythema nodosum that caused painful ulcers on my back and arms. When taken too close to bedtime, I have unusually vivid dreams.

Initially, the dreams contained violent, nightmarish elements. In time, it became a sort of Technicolor version of more typical scenarios. These days, with the fragmented sleep that YOPD has apparently wrought, and general feelings of sadness, I sometimes search for a measure of relief by deliberately taking it right before bed. Whatever dreams I may have on those nights, I want them to entertain me and maybe even bring me comfort. I hope to see the people I’ve loved and permanently lost, especially my grandfather.

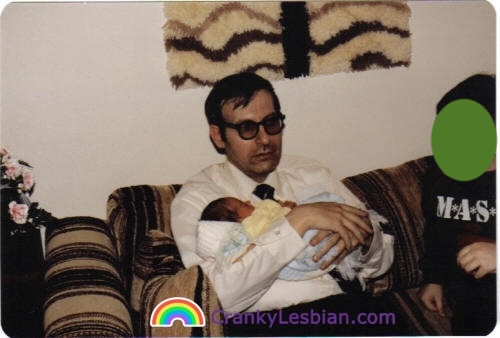

Since his death in my twenties, I’ve regularly dreamed of Papa. At first, I hated to imagine him alone underground, especially in bad weather, and dreamt of the newly disturbed earth of his burial plot as it was covered first in freezing rain and then snow. I was illogically upset that nothing was there to keep him warm. Once I’d adjusted to his absence, he started reappearing in dreams in his usual form, and sometimes in an unusual form — standing fully upright and walking normally, without the use of a cane or walker.

Because of his multiple sclerosis, I’d never seen him like that before. The only time I’d given his physical limitations any serious consideration was when a man his age, the widower of my grandma’s best friend, bounded up to their front door one day as I watched from the window. He looked so strong and capable. “Some people have grandpas who can do that?!” I remember thinking, and for a moment I was sad for Papa and everything he’d lost. But that sadness wasn’t greater than my awareness of all the things he could do that other grandpas couldn’t, like run the board on Jeopardy! or define nearly any word in the dictionary.

Whether or not Papa is healthy in my Plaquenil dreams doesn’t ultimately matter. Often he’s in the background, not doing anything all, and even when they’re more cinematic in nature, my dreams are usually still boring and quickly forgotten in the daylight. But the possibility of seeing him again makes it easier to face another long, potentially sleepless night, and when I catch a glimpse of him — and especially when we’re able to talk — I wake up happy, no interpretation required.